LAWMA Driving Waste Reform With Technology, Enforcement, And Public Partnership

BY BABAJIDE FADOJU

Lagos, Nigeria’s economic powerhouse and Africa’s most populous city, has lived for decades under the weight of its waste management crisis.

Rapid urbanization, an ever-growing population, and inconsistent enforcement have created an environmental challenge that often seemed too entrenched to fix.

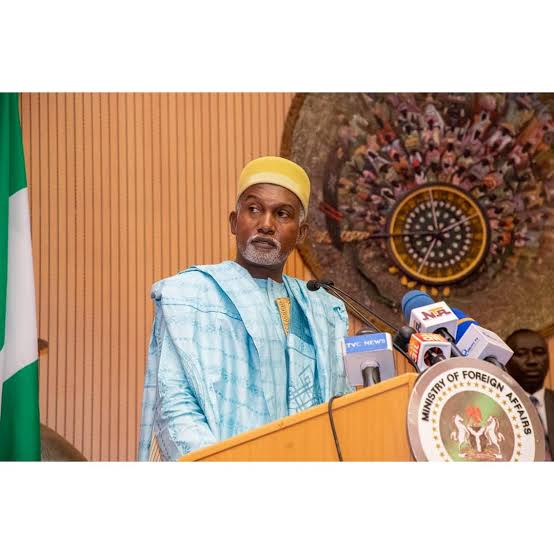

In the past two weeks, however, Commissioner Tokunbo Wahab of the Ministry of Environment and Water Resources has shown that determined leadership, backed by clear policies and strategic partnerships, can shift the trajectory.

The recent surge in activity from the Lagos Waste Management Authority (LAWMA) under his oversight is not cosmetic; it is systemic.

A few weeks later, the Commissioner for Environment and Water Resources sealed a partnership with Siemens Group to expand waste-to-energy capacity in the state. With Lagos generating over 14,000 tonnes of municipal solid waste every day, this move is not merely about clearing refuse; it is about converting a liability into a renewable asset.

Integrating this initiative with existing projects like the Epe waste-to-power plant and material recovery facilities in Ikorodu and Badagry shows an understanding that waste management and energy policy can, and must, intersect. The economic implications are equally significant: jobs in renewable energy, private-sector investment, and reduced dependence on landfill expansion.

But technology alone will not clean Lagos. Enforcement has been firm, and importantly, consistent. On August 9, the Lagos State Wastewater Management Office, acting under the commissioner’s directives, sealed Myca 7 Court in Lekki for discharging raw sewage into public drains, an environmental hazard with direct consequences for public health.

This was no isolated action. From the arrests of offenders in Ajasa Command to warnings of ₦250,000 fines or imprisonment for environmental violations, the current administration is giving real teeth to the “zero tolerance” declaration he made in June.

The difference now is follow-through: offenders are not only warned but apprehended, and the message is spreading that environmental impunity will no longer go unpunished.

Physical clean-up efforts have been equally visible. Between July 30 and August 10, ministry teams cleared flood-prone drainage points in multiple districts: desilting secondary collectors on Ago Palace Way in Okota, opening manholes on Nnamdi Azikwe Street on Lagos Island, and restoring the Akanimodo/Ajelogo/Mile 12 trapezoidal drain in Kosofe.

These interventions are targeted and timely, addressing both the symptoms and the causes of seasonal flooding. Residents have noted the difference; proof that tangible results build public confidence faster than policy statements ever could.

Community engagement has not been left behind. Collaborations with groups such as YOUTH WASH CDS have brought sanitation education to grassroots levels, encouraging better waste habits and advocating for basic infrastructure repairs like functional school toilets. This combination of enforcement and education is critical; without public buy-in, even the best policies risk failure.

The Commissioner has also recognized that institutional capacity matters. LAWMA staff under the leadership of Dr. Muyiwa Gbadegesin have undergone training at the University of Lagos on climate-smart waste management, with a focus on digital tools that improve operational efficiency.

There is even renewed discussion on reviving the once-monthly sanitation exercise, an initiative that, if modernized and properly enforced, could embed cleanliness into the city’s civic culture.

Critics may point out that illegal cart pushers and unregulated waste disposal still thrive in some areas, and they are not wrong. These are persistent challenges that require sustained pressure, not sporadic crackdowns. Yet the pace and breadth of recent measures suggest a coordinated long-term plan, not just reactive interventions.

In my opinion, Tokunbo Wahab’s leadership over the past weeks demonstrates what environmental governance should look like: evidence-based, tech-enabled, uncompromising on enforcement, and rooted in public engagement.

Lagos does not just need cleaner streets; it needs a cultural shift toward environmental responsibility. The commissioner’s strategy lays the groundwork for that shift. The question now is whether residents will match the state’s resolve with behavioural change.

The truth is inescapable: a cleaner Lagos is not a political favour; it is a civic necessity.

The entire Lagos Environmental Team’s recent actions deserve commendation not because they are perfect, but because they show a rare alignment of vision, policy, and execution. If sustained, this could be the beginning of Lagos rewriting its environmental story, from a megacity overwhelmed by waste to one powered by sustainability.